Everytime I do a "favorite things" post, comments regarding my blog seem to skyrocket as if I'm Oprah's whitebread Jewboy cowboy cousin or something. As such, here's what I've been hooked on of late...

Foundling, David Gray-As Peter Gabriel and Paul Simon slink off into VH1 tribute anonymity, we're in desperate need of an artist who can blend mainstreams sentiments with worldly eclecticism. Foundling is the album Gray's been building toward his whole career-it has all of White Ladder's creamy harmonies but none of its overproduction, twice the orchestral genius of Life in Slow Motion but only a quarter of its self-indulgence. This is a prime example of artist as mad scientist, integrating influences without flaunting them (the title track has just the right dose of career-peak Genesis to liven the sad-eyed mysticism of the lyrics) and straddling the fine fine line between ballsy experimentation and tried-and-true technique ("Forgetting" has a pop-muzak hook bound to give Chris Martin a hard-on, but also boasts a rhyme scheme the likes of which you've never heard before). In short, its an intelligent, intoxicating helping of guilt-free pop. Hallelujah. Listen to "Forgetting"

Opposite You, Marin Mazzie, Jason Danieley-Not since Kurt Weill and Lotte Lenya has the Broadway boasted a more boffo golden couple. Her spinny soprano and his robust tenor blend gorgeously on this marvelous meringue of a duets album. Offstage, they're absolute sweethearts (I've met them AAAAH) and onstage they're remarkable versatile, headlining in everything from Ragtime to Curtains to their current hit, Next To Normal. They're just as boundlessly brilliant in the recording studio as well; Jason socks over a ramped-up patter piece ("I Want To Be") just before turning in a stirring, Goulet-esque rendition of a Jerry Herman weepie ("I Won't Send Roses"), Marin feels equally at home with a cheeky pop serenade ("A Sorta Love Song") and an obscure old Streisand ballad ("Who Are You Now"), and together they successfully tackle everything from vaudevillian kitsch ("The Aba Daba Honeymoon") to an exhilarating ten-minute Sondheim suite. Those whose theatre knowledge stops at Phantom of the Opera may very well be the definition of bored for these 45 minutes. But for those who know their showtunes, appreciate vocal technique and go gaga over dramatic singing done 100% right, Opposite You is the opposite of hell. The twosome in concert.

"The News From Lake Wobegon" Podcast, Garrison Keillor-Lake Wobegon, Minnesota-"where all the women are strong, all the men are good-looking, and all the children are above average"-is one of the great fictional locations in pop culture. For the past 20-odd years Garrison Keillor's been exploring the lives of its denizens in a weekly segment that serves as the centerpiece of A Prairie Home Companion, perhaps the last Great Traditional Radio Show. Every one of Keillor's fifteen-minute monologues washes over you with the warmth of a home-cooked homily, albeit one freed of the squirmy specifics of religious judgement. He incorporates stand-up comedy and potent pathos, quotes Shakespeare and bluegrass, explores botox and the Bible and everything in between. Listening to Keillor is like sitting by the fading campfire with a slightly tipsy grandpa who gets off-topic over and over, but does so with such drama that you don't care how far he strays from the original narrative. In one of my favorite monologues, Keillor starts out discussing his oddball sister, exalts the virtues of banana bread, plunges headlong into his boy scout days when he got lost and had to search for a spot to take a piss in the freezing cold, recalls the reappearance of a long-lost family member, and concludes with a gentle plea for compassion and forgiveness. In another, he muses about migration, tells of a Wobegoner's heartbreaking excursion to the city, explains a crotchety old man's disillusionment with the Lutheran church ("Trinity? I don't think so."), proffers his opinions on vodka, botox, and religious trends, and caps the whole thing off with a celebration of American motherhood. It's all over the place, and all of it is abusrd, but it's shot through with an urgent poetry and simple humour that makes it steadily addicting. You'll tune into "The News" more than once, I guarantee it. Prepare to be hooked.

Translations, Sylvie Lewis-This plays like Norah Jones on steroids-or Nellie McKay on relaxants, depending on your viewpoint. With this, her sophomore album, Lewis proves she's here to stay as a major songwriter. Tricks that could seem gimmicky if attempted by other artists-writing as an omniscient figure ("Say In Touch") or taking the POV of a desperate man-child ("Of Course, Isabelle")-are pulled off here with style to spare. Throughout the album, you'll shake your head in disbelief at her adept wordplay (my favorite couplet? "You flirt like a married man/The way you do it only the married can"). It doesn't hurt that these arrangements are gorgeous-it's a kick to see country twang and cabaret class mingle so freely. And that voice, while a little thin, is undeniably expressive. The album won't change your life. But, to steal the title of one of Lewis's best songs, it's "Something to Dream To". (Sorry, no quality Youtube recordings)

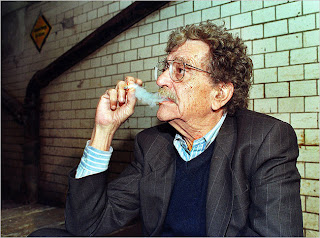

"Harrison Bergeron", Kurt Vonnegut-A world with no competition-paradise, right? Not according to post-modernism's piss-n-vinegar grandpa. In seven stunning pages, using only two characters, a living room and a faulty TV, Vonnegut maps out a doomy dystopia that gives Orwell a run for his money. In this sterilized hell, the best and brightest are saddled with mental and physical handicaps so we're all at the same stage of collective commonality. This ranks with Kurtmeister's best writing, and therefore, some of the best writing ever done. AHHH READ